On January 30th, the Edmund Burke Society at the University of Chicago Law School released an event promotion for an immigration debate to be held Tuesday, February 6th, at 7:30pm at Ida Noyes Hall on UChicago’s campus.

In promoting its “debate”, the organization trivialized the issue and mocked people who are directly impacted by immigration policy. The Society called immigrants “other nations’ wretched refuse”, “Chinese entrepreneurs pursuing Fortune’s cookie,” and posited that “no engineer is worth the drag of a freeloading cousin.” Even in representing an ostensibly pro-immigrant stance, the flier’s authors ask, “[W]ithout foreign labor and grit, who will build the wall?”

The Edmund Burke Society’s event promotion denigrates and dehumanizes immigrants everywhere. Instead of opening a meaningful dialogue, it legitimizes the racist and xenophobic ideals we have seen rise to power in the past year. As institutions of education, law schools should fuel inclusion and serious conversation, not host racist and demeaning rhetoric.

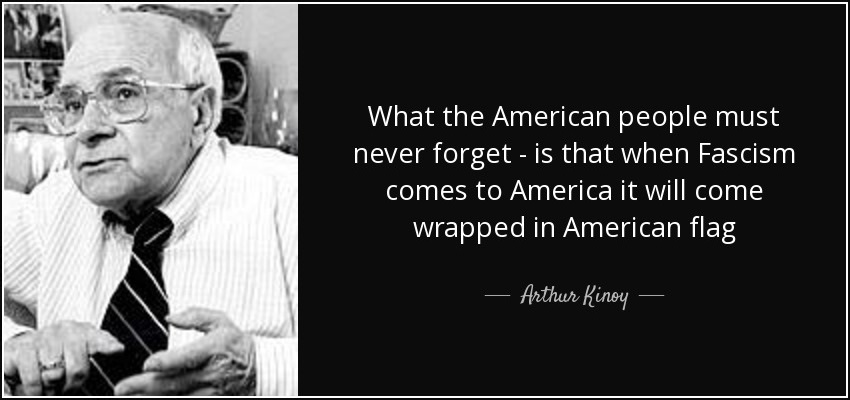

The National Lawyers’ Guild – Chicago Chapter stands with immigrants unconditionally. This abhorrent rhetoric is exactly what the NLG, in Chicago and across the nation, has fought against since its inception. We condemn the Edmund Burke Society’s rhetoric in the strongest terms possible and encourage our members to stand up against hateful speech wherever they encounter it.

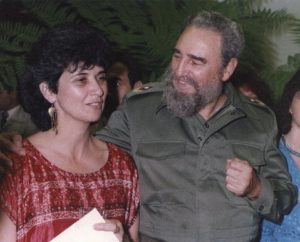

She left DePaul University in 1992, and joined the New York City law firm

She left DePaul University in 1992, and joined the New York City law firm