This year the National Lawyers Guild is honoring Bernardine Dohrn for the Kinoy Award at our Annual Celebration. We are grateful for her steadfast and decades long commitment to the struggle for justice and global equality and her tireless mentorship of the next generation of people’s lawyers.

Here Bernardine Dohrn tells us of her work with the Guild, and shares a chapter from her book, Race Course: Against White Supremacy.

I moved to New York City to work as the first NLG law student organizer right out of law school, in June 1967. We argued that law students and lawyers could and should be part of the Movement, as well as legal defenders of the movements: struggles against the imperialist war against Vietnam, against the draft and military injustice, in support of the Black Liberation movement including political prisoners, SNCC and the Black Panther Party. We mobilized legal support for mass arrests at the Pentagon, demonstrations against Dean Rusk and Robert McNamara, GI’s returning their medals, the demands of Black Student Unions for African American history, culture, faculty and open enrollment, for an end to secret university war-releated research and their occupation of neighboring Black communities. We urged support for living wages for university staff and employees, and the rights of Black workers in DRUM. As I travelled to law schools across the country, law students eagerly establish NLG chapters to focus their work, and the NLG took root among radical lawyers and flourished.

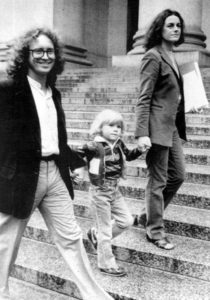

After a decade as a federal fugitive on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list I was subpoenaed and called before a federal grand jury investigating the Brinks robbery in Manhattan in 1982. Two of the persons charged in the Brinks robbery were Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert. Due to their imprisonment, their 14 month-old son, Chesa Boudin joined our family as our third son, and always visited and maintained his close relationships with his biological parents, Kathy and David. The narrative below tells that story.

Excerpt from Race Course: Against White Supremacy,

by Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, Third World Press, 2009

Chapter: The Modern Slave Ship, by Bernardine Dohrn

“I did time in the federal correction center while the {3} children were young, and they visited me separately each week. With Zayd, who was five, I did elaborate homemade crossword puzzles, we read books, and then talked about why the other women in the visiting room were incarcerated, and who was visiting them. He jumped into my arms to tell me about the long wait downstairs, the searches, and the ways in which guards shouted to waiting families about dress codes and contraband. He sat on my lap for the whole visit, and when he left with the comforting friend who always brought him, he would wave to me from across the street until I flashed the lights in my cell as a final goodbye.

Visits from two-year-old Malik were excruciating but deeply satisfying. He almost always went directly to sleep in my arms, so I could breathe in his toddler smell and nuzzle his cheeks and neck, examine his hands with impunity. Although he was verbal and articulate, able to say that his suddenly new brother Chesa “can’t have my mommy,” he chose silence during our visits. Chesa, already visiting his biological parents in prison as a one year old, visited me less often.

The Metropolitan Correctional Center is at the edge of Chinatown and across from the New York City Police Headquarters in Lower Manhattan. From certain cells, we could see the Brooklyn Bridge. Only one floor of the tall, narrow pre-trial building housed women: we were some eighty women in a prison of more than a thousand men. That made every venture away from our unit an unpredictable voyage: entry into a packed elevator of male prisoners and guards; processing in the lawyers’ visiting area with shouting male voices vying to hear each other; unexpected conversations in line waiting to see a medic. Because none of us were yet convicted, we did not endure the routine strip searches and internal examination of bodily cavities that characterize women’s prisons, nor were we routinely subjected to sexualized violence.

The women on our unit were African American if they lived in New York City, or Latinas direct from Colombia or Mexico who spoke only Spanish. The women from Latin America had seen only Kennedy Airport and the MCC in North America; they cried and said rosaries and were humorously willing to try to teach this ignorant gringa Spanish. All were charged with carrying drugs into the U.S. as “mules”; none were major or even regular drug dealers but each had taken one crazy, terrible risk, in the hopes of getting money to help their children have better lives. The women were being prosecuted primarily to “flip” them, to give evidence against male higher-ups. There was no word then for globalization but these women were an advanced wave of the so-called war on drugs and the escalating incarceration and criminalization of women. At the current rates of incarcerating women, there will be more women in prison in 2010 than there were all prisoners in the U.S. in 1970. Such is the taken-for-granted of what passes for crime control.

My closest friend was Cheryl, ten years older and able to beat me regularly at Scrabble. Cheryl spent a good part of the day on the pay phone; she was openly proud that her craft (hotel boosting, or robbing hotel rooms) required wit and never violence. Cheryl taught me to count to ten slowly whenever it appeared that a fight was jumping off between women prisoners, and she schooled me in the fact that women were likely to shout, to get in each other’s faces, but that if a punch had not been thrown by the number ten, it would stay verbal. In fact, the women on the unit were generous and kind to one another, organizing efficiently to nurse a new prisoner who was detoxifying and miserably sick by sitting with her in shifts, sponging her face, offering clean sheets. They knew how to get through holidays together. We shared books and cosmetics. We plotted how to get out along with the (all male) guards if there were a fire in the building. Some were geniuses at sewing and making the miserable navy blue uniforms look tight.

My term in prison was indeterminate and bizarre. I was jailed for refusing to obey the order of a judge to cooperate with a federal grand jury by giving samples of my handwriting. I was held in civil contempt of court, although my lawyer and I argue that the government was in possession of rooms filled with my handwriting, since they had seized files and letters from my apartments during COINTELPRO, a secret and illegal FBI program), and I had subsequently been a federal fugitive for eleven years. It was anguishing to be separated from our young children, but I saw resistance as a question of principle. During our years outside the law, scores of people refused to cooperate with grand jury witch hunt, organized to try to find members of the Weather Underground. The government grand jury strategy failed because ordinary people, innocent people, refused to cooperate. I could not do differently, even in different circumstances.

The dilemma was that there is no sentence when you are held in contempt. The idea of the prosecutor is to coerce your testimony, a relic from the British Star Chamber proceedings. So we (there were fifteen women who defied the grand jury, all of us at MCC) were ordered to be held until we cooperated, or until the U.S. attorney decided to indict us, or until their interest moved on to other matters. I had been back in ordinary life, above ground, for just a year, working as a waiter, then at a law firm, being a mom of three boys, and thinking about how to reinvent myself as an activist at the age of forty. Bill visited me every single day, parented three small children, and tried to cope.

As it turned out, I served just seven months. I was released on a motion that argued that since I would never cooperate, because I was willful and stubborn, the contempt sentence had become “punishment” instead of “coercion”. The other grand jury women were similarly released, or were charged in huge RICO conspiracy indictments. I thought I would never forget my prison number, never want to read another murder mystery, or do yoga again. But back with my family, we began the prison visits with Kathy and David that would characterize the next twenty years.”

The National Lawyers Guild is proud to be presenting the Kinoy Award to Bernardine Dohrn. For our 80th Anniversary, show your support for the Guild by buying a ticket!